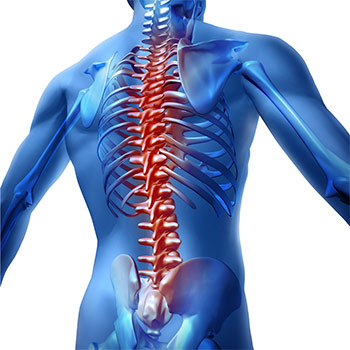

Every day, you are at risk of debilitating back pain.

Frequent bending and twisting in the spine is one of the main causes of back pain, but it’s also completely unavoidable in everyday life. This is why we’re so concerned with not just being careful with your spine, but training it to withstand whatever life can throw at it.

As you might have guessed, today we’re going to discuss bending and twisting, the risk they pose to your spine, and how you can avoid a lifetime of debilitating lower back pain (LBP).

Physical Characteristics

The spine is designed to bend and rotate.

However, problems tend to occur in these movements. Adding weight to them or performing them without much practice is one of the most common ways that you are at-risk for debilitating pain and injury. Needless to say, that’s a bad thing.

This is because the spine is strongest in the neutral position, and bending/ twisting are deviations from this position. In most people, the neutral and rotated/bent positions are both weak, but the latter more so.

Stability in the spine comes from effectively controlling, limiting, or using these positions and movements. This is why we can say two things that sound contradictory, but they’re both true:

1. Excessive bending and rotation of the spine under load is a common cause of injury

2. You should probably be doing more bending and rotating of the spine under load

This is because, while this is the cause of many injuries, the problem is that you are weak and un-practiced in these movements and positions. As ever, the problem is that the body is not prepared for these movements and not that they’re inherently bad for you!

The point of this article, then, is to guide you through how to avoid these issues, protect you from injuring your spine, and develop a great core along the way.

Step 1: Strong Neutral Position

To start with, you actually need to have strength and control in the core. These are the basis for any movement in the spine and they insulate it against the worst of the movements you’re going to perform in day to day life.

If you’re not strong in the neutral position, it’s nearly impossible to strengthen and control other movements.

So, what is neutral spine position?

Put simply, it’s a range of healthy and efficient load-bearing positions that your spine has evolved to sit in. It’s the position where you have a relatively flat back, with a very slight curve in the lower spine:

Figure 1 – Neutral Spine Range

If you can’t find and hold this neutral position, you’re not ready to do much else; the spine is crucially important and strengthening this position should be your first priority.

This is the starting point for good posture, and the basis for effective movement in simple movements found in weight training. It’s the basis of things like the squat, deadlift, and row, where we want to maintain a neutral spine and move other parts of the body.

We find a comfortable neutral spine position with practice controlling the muscles of the core and glutes. This is a practice that may take a little while, but is a life-long pursuit of constantly strengthening the position, so just find it and work on it initially.

You can start this process by moving through the range with exercises like the cat-cow, which help to get the spine moving through it’s full range. From here, you should be finding a position somewhere in the middle of the rounded and arched position.

From here, you can practice with very simple movements like the plank, where neutral spine is the focus of the exercise. This will improve both familiarity with the position and the strength/control required to hold it. This is crucial when we move onto the next steps.

You should also work on movements like paused back extensions, lying leg raises, and knee tucks to work on strengthening the core in the neutral spine position. This is going to be helpful for stabilizing the spine in general, and specifically in the movements we’re going to transition into!

Step 2: Practice Anti-Rotation

Now you’ve got a neutral spine position figured out, you can start using that position to resist rotation. This is the easiest and most intuitive way of developing rotational strength since it doesn’t actually require you to move through rotation just yet, and is based on the simple stability-strength developed in the neutral position.

The idea is to put some rotational demands on the spine, resist them, and thus train the muscles involved in rotation. These are crucial exercises for developing the basic strength and stability to keep the spine under control against rotation but also for performing rotation.

We start this with the simplest anti-rotation exercise you can perform in the neutral position: the dead-bug. This is the best starting point for rotation training, since it’s bodyweight, it’s easy to figure out if you’re doing it right (the spine should be flat to the floor), and you can easily progress it.

Start with the leg-only deadbug, lowering a single leg to the floor slowly, then returning it to the starting 90-degree position. After you’ve gotten this, you lower the opposite-side arm at the same time, which places a rotational demand on the body; simply stay in neutral against this demand.

From here, you can work on bird-dogs, which are more challenging and require you to find neutral without the aid of the floor on your spine. They’re also just more challenging from a leverage stand-point, so they help to strengthen the muscles of the core, back, and glutes in rotation/anti-rotation movements. These develop strength in the neutral/anti-rotation plane using leverage, but you can also use bands for this.

For example, the band-resisted side plank is a great way of adding some more loading and challenge to the anti-rotation movement pattern. This is a great – but challenging – way of building beyond the simple dead-bug/bird-dog exercise system.

A similar example is the Pallof press: a simple exercise found in the programs of many sports strength and conditioning programs. This is performed against a band or cable machine, which can help scale the difficulty to your personal strength – it’s a good exercise but does require some basic anti-rotation strength – so don’t rush to it.

Step 3: Strengthen Rotation and Anti-Rotation

Once you have a strong neutral position that is able to resist rotation, you can make some serious gains and protect your spine with deliberate rotation movements. These are movements under your control that allow you to strengthen the position and build familiarity with rotation. These offer significant benefits for movements like sprinting, but also prepare the spine and the surrounding musculature, building stability in these otherwise-risky positions.

Simply put, you’re going to be safer in positions that you’ve trained. The additional strength and control count when you’re using them during everyday life, whether it’s playing with the kids, gardening, or moving cumbersome objects.

Rotation training starts with 2 key exercises that are going to be fantastic for building strength and control in rotation: the side plank with a twist, and the lying rotation. If you’re struggling the position itself (mobility, not just strength), you can also practice some seated t-spine twists.

These movements build the basic movement pattern, focusing on slow and controlled movement. This should come before any loading, and offers a strong foundation of movement. This alone could help the average joe prevent a number of spinal injuries; and is the basis for gymnastic strength training in spinal rotation.

From here, you can add rotations against a band, similar to in the previous section on anti-rotation. Movements like wood-chops or side plank twist against a band can offer great bang-for-your-buck with very little equipment, but huge effect!

These continuous-tension movements are great for ensuring you’re controlling the whole range and never not being deliberate about your movement. This is key, because you need to strengthen the whole range (and especially the end-range) of rotation to prepare for future movement. After developing this strength with elastic or constant-tension resistance, you can work with free weights. These are the most tricky to get working, but the most easily-scaled form of resistance for rotation.

Movements like Russian twists are a good example of this, where you can build significant strength in the core for bending and twisting. You could also perform balance ball rotations with a dumbbell for extra load, or rotating lunges, all of which develop comfort, confidence, and strength in rotation.

Final Thoughts

Being weak in any movement makes it dangerous. We don’t need to hide from rotation, it’s going to happen, but we do need to be in control of it.

Strength and familiarity in rotation are the keys to reducing the risks that it poses, and the injuries that are so common place. Being practiced is the key, and we’ve outlined a simple plan on how you can achieve this.

It’s not going to be a magic fix and injury may still happen. Preparation will take time, but you can prepare yourself for movement and get stronger along the way. That sounds like a win-win to us!

Rotation work can be added in at the start/end of a session for warm-up/cool-down, and a little bit of direct rotational core work could be as simple as 1-3 sets of the exercises listed above. You could even just perform a 2-5 minutes core circuit at the start and end of every day, and still see great results.

The options for rotation strength are easy and varied. The other alternative is weakness and injury.