The term frozen shoulder is a complicated one and it comes from a mixture of factors; some from the joint, some muscular. And it’s a tricky one to fix.

What we’re going to do in this article is breaking it down into common symptoms, possible causes, and a general idea of how to get started fixing it. If you have any significant pain or are coming to this from a prior injury, go see your doctor.

In the meantime, let’s figure out what a frozen shoulder is and how to know if your shoulders are ‘frozen’…

What Is It?

More often than not, frozen shoulder refers to a condition called adhesive capsulitis, though there are many other conditions confused with this. These could include muscular problems and thickening of the tendon, so don’t rush to a conclusion.

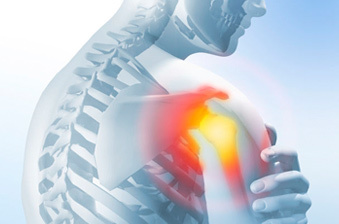

Frozen shoulder can occur in response to a wide variety of problems and may be a gradual or instantaneous onset. When it comes to symptoms, the classics are restriction of movement, but in both active and passive ranges. This means that you’re not just lacking control over the joint, as you might be with poor mobility. This passive difference is usually how we identify frozen shoulder, since it suggests there are significant structural problems in the shoulder itself.

The idea of AC is often the thickening of joint tissues, severe inflammation in the joint itself, or aggravation of existing injuries. If you’ve experienced damage to the acetabulum before, or have had recent surgery, frozen shoulder is more likely to occur.

There are, however, a few more things we can point at as risk factors but they shouldn’t be seen as causes:

· Being female, seemingly

· Diabetes

· Previous stroke or TIA

· Prior injury or impingement

· Existing conditions related to tendon/connective tissues thickness or pliability

· Cancers and other carcinoma’s

· Complex regional pain and chronic pain syndromes

These are contributory risk factors that don’t determine your condition, but they are where we see frozen shoulder happening most commonly.

Symptoms/Causes

It’s really hard to separate out the causes and symptoms in shoulder problems like frozen shoulder. In many cases, we’ll see gradual onsets of tightness, pain, and restriction to the joint, making it hard to say where it started or how it developed.

The symptoms used to define frozen shoulder are pretty simple by themselves, but we don’t get to see many of them without surgery:

· Loss of crucial connective tissues in the shoulder

· Small joint size – either genetically or due to reduced joint space over time

· Infection or disorder of the synovium around the shoulder joint

· Damage or disorder of the rotator cuff, though this could be a symptom rather than cause

Obviously, these are all tissue problems that you won’t see without opening up your shoulder. As a result, it’s pretty hard to speculate on what exactly is going on until it’s too late and you’re in surgery.

What we know for sure is that your shoulder is producing, stiffening, and often inflaming tendons and other connective tissues without much reason. This is why the shoulder feels “frozen.” The tissues are growing and stiffening in a way that isn’t aligned with your use of the shoulder.

Let’s look past these confusing diagnoses towards what you can do about it, because that’s what really matters…

To deal with a frozen shoulder, you need to know where you are in the lifecycle. There are 3 stages we want to look out for during this process, because they’re the standard lifecycle of frozen shoulder.

1. Onset and Freezing

This is simply the process during which the shoulder begins to show problems; it could be when freezing starts to get painful, or immediately as it’s setting in. For many people, it might not be caught until it’s too late if shoulder movement isn’t a part of a regular, active lifestyle.

2. Frozen

This is the stage where the shoulder itself is already in a bad place. It’s the bit of the condition that many people are living through while reading this article.

This is the time where it’s too late to prevent the problem, and management/pro-healing measures are the way to go. From here, it’s time to take care of your shoulder and look towards therapeutic/clinical measures.

3. The Thawing Process

This is an extended analogy, but the idea is that frozen shoulder tends to come undone with time. Fortunately, this is not often a lifelong problem. It may take years, but it’s better than a long-term problem with your shoulder joint!

This is where you want to be, and the proper management of the shoulder and the rest of the lifestyle around it can accelerate the process. Tentative but progressive measures like those outlined ahead are the way to go.

Step One: Don’t Muck It Up

The ultimate principle of dealing with a frozen shoulder, and most other significant conditions, is to not make it worse. If you manage that, you’re already winning. The body has a great restorative system and simply not-aggravating the shoulder is step one.

Stop doing whatever hurts it or leaves you with excessive soreness/restriction. This could be sports, it could be part of your work, or it could be your leisure activities. Whatever makes it worse, cut it out.

Step Two: Patient Movement

One of the things we know for sure is that immobility with a frozen shoulder condition is a bad thing. We want to seek the most amount of activity that you can comfortably do, with the situation as it is now.

That means NOT immobilising it entirely, but working well within the range that you have. We don’t want to overload the joint, but consistent and healthy movement will contribute to better nutrient delivery and, possibly, improve capsule response.

Stay away from anything causing you pain, and load patiently. We don’t want you busting out a max bench press. That’s not the kind of motion we’re looking for. Gentle movements, loaded comfortably, and with an eye to moving well within the range you can achieve right now is how you want to go about this.

Strength should focus on proper stability in pain-free ranges and especially isometric work. Simply holding weight in position can produce great change in the shoulder joint, and may allow the capsule a restorative stimulus without too much weight or risking uncomfortable movement.

Step Three: Ensuring Comprehensive Joint Health

During times of restricted movement, especially in external rotation which is common for frozen shoulder, it’s important to take care of both shoulders.

Around 20-30% of people with frozen shoulder will cause compensatory or concurrent problems in the other shoulder. Equally, the poor positioning the shoulder gets stuck in could add longer-term issues like rotator cuff damage or impingement.

During this time, be sure to perform mobility work around the shoulder whenever you can do so, without pain. This helps prevent secondary problems off the back of frozen shoulder, such as RC tears or general tendon degradation when the frozen shoulder passes.

Easing potential burdens on the shoulder and better joint spacing through stretching in common tight areas, like the traps, chest, and biceps tendons can help alleviate some pressure. This isn’t a sure-fire fix, but it contributes to the healing process positively anyway.

Step Four: Ensure Effective Thawing

As you move into the final stage of the condition, the time during which you’re watching it improve, the main thing is to be careful. It may feel like everything’s getting better but patience with the new range of motion is important for the joint and the surrounding structure.

As you regain comfort in your new ROM we recommend taking it slow and really practicing that ROM patiently, always keeping an eye on where pain begins. We want you to work control and strength there, since it’s easy to re-injure yourself in other ways after a return to increased range.

This range may not have been practiced and controlled in a year or more, so it’s fair to say it’s more injury-prone. Strengthening and controlling are key and light shoulder exercise should work to familiarise, stabilise, and strengthen that range.

On top of this, be sure to keep yourself mobile and limber. As you regain these new ranges it’s going to be crucial to avoid alternative problems through impingement and similar, as well as existing demands on the shoulder from the chest or traps, for example.

Your recovery should be equal parts strengthening and mobility. This ensures proper maintenance of your new ROM and improved control of the processes around the shoulder joint itself.

Final Thoughts: Take Care Of Your Healthy Shoulders!

When the time comes that you’re eventually free of the condition, it’s important to take care of your shoulders.

It’s easy to take healthy range for granted but it’s important to maintain it and appreciate it. Frozen shoulder is a sign of things to come if you don’t take care of yourself. Proper joint space, mobility, strength, and control through the shoulders impacts your life in a big way.

The kind of restriction you felt during frozen shoulder could re-surface in later life due to muscle loss and similar issues. Maintain your shoulder health program long after frozen shoulder, even if only to prepare it for aging and ensure that problems don’t persist in the long-term.

The shoulder is a mobile and difficult joint, and it’s an at-risk joint for many people. Investing a little time is all it takes to produce healthier shoulders and it can yield amazing results in pain-free living for years to come.